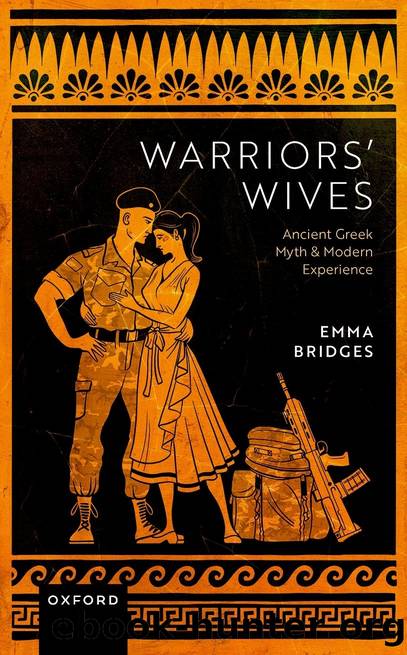

Warriors' Wives by Emma Bridges;

Author:Emma Bridges; [Bridges, Emma]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780192581600

Publisher: Oxford University Press USA

Published: 2023-08-09T00:00:00+00:00

Aeschylusâ Clytemnestra

The story of Clytemnestra has enjoyed a particularly rich afterlife, thanks largely to the attention which Aeschylus gave to her relationship with Agamemnon in his 458 bce trilogy, the Oresteia (comprising the tragedies Agamemnon, Choephoroi, and Eumenides). As discussed in Chapter 2, Agamemnonâs sacrifice of his and Clytemnestraâs daughter Iphigenia for the sake of pursuing war against Troy might represent metaphorically the challenges faced by couples when the demands of the military take precedence over those of a soldierâs partner and family. This mythical marriage, as scrutinized by Athenian tragic dramatists, can also be read as an extreme manifestation of the fears of troops on active service that their place at home might be filled by another man in their absence. In Chapter 5 I will analyse in detail the representation of Agamemnonâs return as a distortion of the normal processes of reunion between returning husband and waiting wife; there I will explore further Clytemnestraâs refusal to relinquish her role as head of the household, and consider how this relates to her transgression of gendered norms. For now, however, I consider the way in which infidelity is represented in the Agamemnon, and in particular how Aeschylus draws here on the Homeric comparison between Clytemnestra and Penelope. In this playâin contrast with tragedies by Sophocles and Euripides, which I will discuss briefly later in this chapterâClytemnestraâs relationship with Aegisthus is given less weight as a motive for murder than her desire to take revenge for Agamemnonâs sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia. For Aeschylus, Clytemnestraâs infidelity is just one element of this waiting wifeâs transgression of societal norms, and of her failure to behave as a warriorâs wife should. I will also consider in this section what the Agamemnon suggests about Clytemnestraâs perspective on her husbandâs extramarital relationship with Cassandra, the war captive with whom he has returned home.

Although infidelity is not cast here as the primary motivation for the murder of Agamemnon, the shadow of Clytemnestraâs adultery is present throughout Aeschylusâ Agamemnon. The watchman comments in his opening speech that Agamemnonâs house is ânot tended very well as in the pastâ (οá½Ï á½¡Ï Ïá½° ÏÏÏÏθâ á¼ÏιÏÏα διαÏÎ¿Î½Î¿Ï Î¼ÎÎ½Î¿Ï , 19; cf. 36â7, where he suggests that he is unable to speak out about the houseâs troubles); this appears to be an oblique reference to Clytemnestraâs behaviour. In his representation of Clytemnestra Aeschylus plays with the image of the good and faithful waiting wife, drawing on the Homeric precedent which sets her up as Penelopeâs opposite. For example, Clytemnestraâs opening words in the play, and her exchange with the chorus, where she expresses joy at the news of Troyâs fall (264, 266â7), are duplicitous; the listening chorus cannot yet know that her delight stems from the fact that she can now carry out her plan to kill Agamemnon.36 She later articulates a response to her husbandâs homecoming which combines all of the elements that her listeners (the chorus as internal audience, and the spectators in the theatre) might expect from a loyal wife (601â12):

Iâll rush to receive my honoured husband as well as possible on his return.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell & Bill Moyers(936)

Half Moon Bay by Jonathan Kellerman & Jesse Kellerman(920)

A Social History of the Media by Peter Burke & Peter Burke(886)

Inseparable by Emma Donoghue(854)

The Nets of Modernism: Henry James, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Sigmund Freud by Maud Ellmann(772)

The Spike by Mark Humphries;(730)

A Theory of Narrative Drawing by Simon Grennan(712)

The Complete Correspondence 1928-1940 by Theodor W. Adorno & Walter Benjamin(711)

Ideology by Eagleton Terry;(665)

Bodies from the Library 3 by Tony Medawar(656)

World Philology by(649)

Culture by Terry Eagleton(648)

Farnsworth's Classical English Rhetoric by Ward Farnsworth(647)

Adam Smith by Jonathan Conlin(618)

A Reader’s Companion to J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye by Peter Beidler(616)

Game of Thrones and Philosophy by William Irwin(604)

High Albania by M. Edith Durham(598)

Comic Genius: Portraits of Funny People by(588)

Monkey King by Wu Cheng'en(581)